Welcome to *special edition* of Creature Feature, a series from the CELT education team highlighting local wildlife. Each week, we will share a short introduction to a local organism that you might encounter in your backyard or on our trails.

This week, we’re featuring a creature that isn’t quite as beautiful as some of our previous features. In fact, it may be the most repulsive creature yet: ticks. Most people know to be careful of ticks, particularly in the spring, but that’s about it. I truly think this is a subject where learning a little bit more will help you be less afraid, better informed, and most importantly, safer. Without further ado, I invite you to tuck in your pants, put on your bug spray, and prepare yourself to get to know our tiniest enemies.

First, the basics.

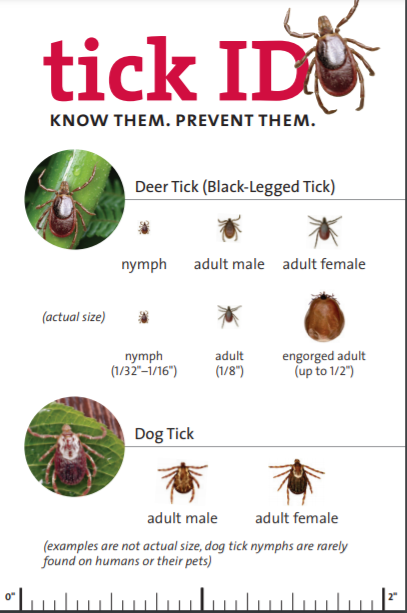

Ticks are arachnids, not insects, meaning they are similar to other 8-legged critters like spiders and mites. There are actually 15 species of ticks in Maine, but there are only three that you are likely to encounter. According to the University of Maine Cooperative Extension Website, which also happens to be PACKED with useful information, the three most common ticks to encounter are the Blacklegged Tick or Deer Tick (Ixodes scapularis), American Dog Tick (Dermacentor variabilis), and Woodchuck Tick (Ixodes cookei). The other 12 species either don’t attach to humans or aren’t present in sufficient quantities to warrant spending too much time on here, but the curious can learn more at the UMaine website.

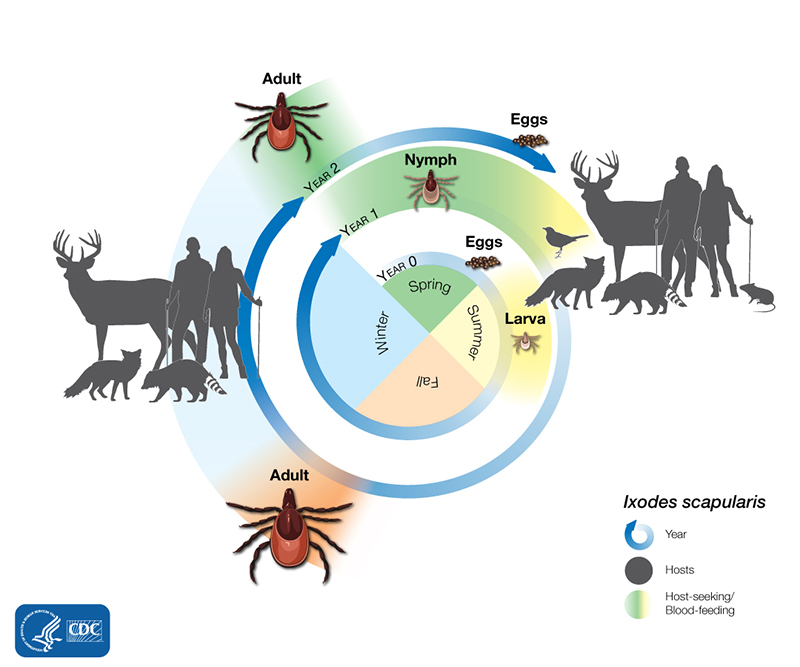

Ticks have a pretty strange life cycle compared to most organisms. In the first stage of development, eggs hatch into larva. The larva are tiny – smaller even than adult deer ticks, the smallest of the common ticks. The larva will attach to a small animal – usually a rodent or other small mammal, and almost never a human – and eat it’s first “meal.” It will then go into dormancy over the fall and winter in preparation for spring.

By spring, the larva has developed into its second stage, the nymph. The nymph stage is still smaller than the adult, which can make them hard to notice. However, this stage is big enough to feed on larger mammals, like deer, dogs, or humans. This is also where the danger begins. If the animal that the larva attached to had any diseases, the nymph can pass those diseases along to the new host.

Similar to the larva, by fall the nymph will go into dormancy and emerge as an adult in the spring. This is the stage at which ticks are most easy to identify, as they have reached their final size and coloration. See the image at right for a good visual example of what deer and dog ticks typically look like.

Let’s talk diseases. If you know anything about ticks, you’ve probably heard of Lyme disease. This is the most common disease transmitted by ticks, and is present in approximately 44.7% of all black-legged ticks in Maine, according to a 2020 statewide sampling program. Other common tick-borne diseases include anaplasmosis (11.3% of ticks) and babesiosis (12.4% of ticks).

Note: Other species of ticks can carry diseases, but currently this only happens at much lower rates. Most of the risk to humans comes from black-legged (deer) ticks.

The good news is it takes more than contact with a tick to transmit any of these diseases. All three of these diseases are transmitted by bacteria. In order for a tick to infect you, it needs to bite you and stay attached long enough to transfer some of those bacteria into your bloodstream. While opinions differ on how long this may take, the CDC says that in most cases the tick must be attached for 36-48 hours. Consequently, one of the most important defenses against tick-borne disease is…

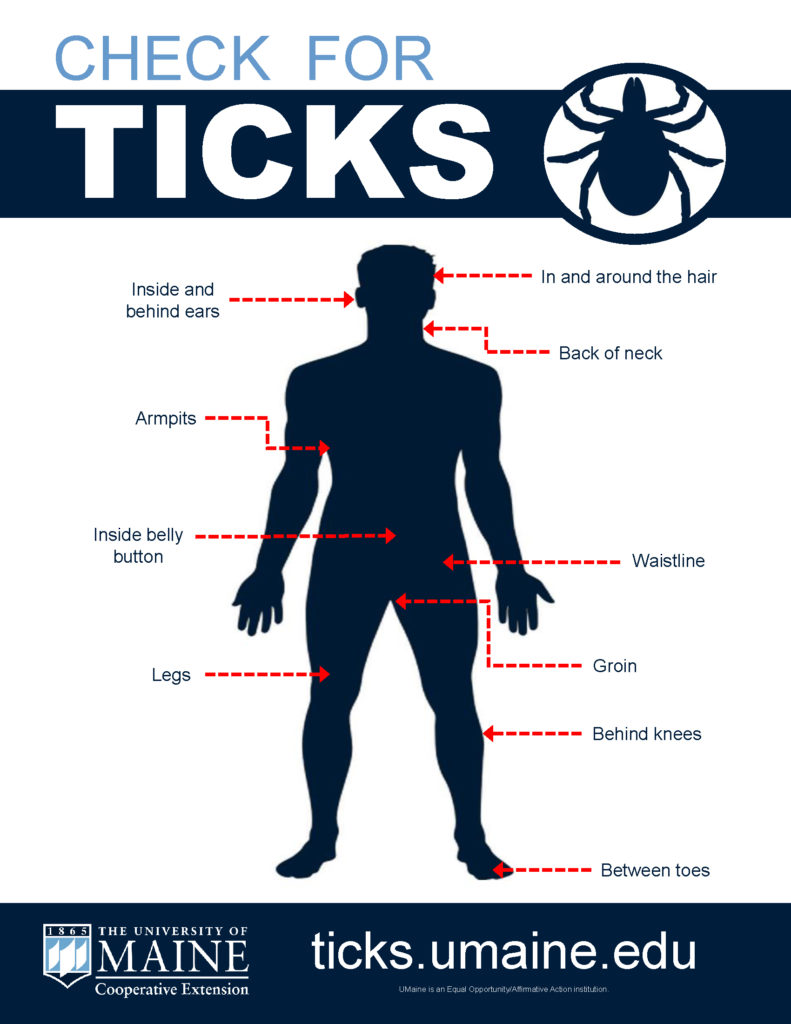

Tick Checks

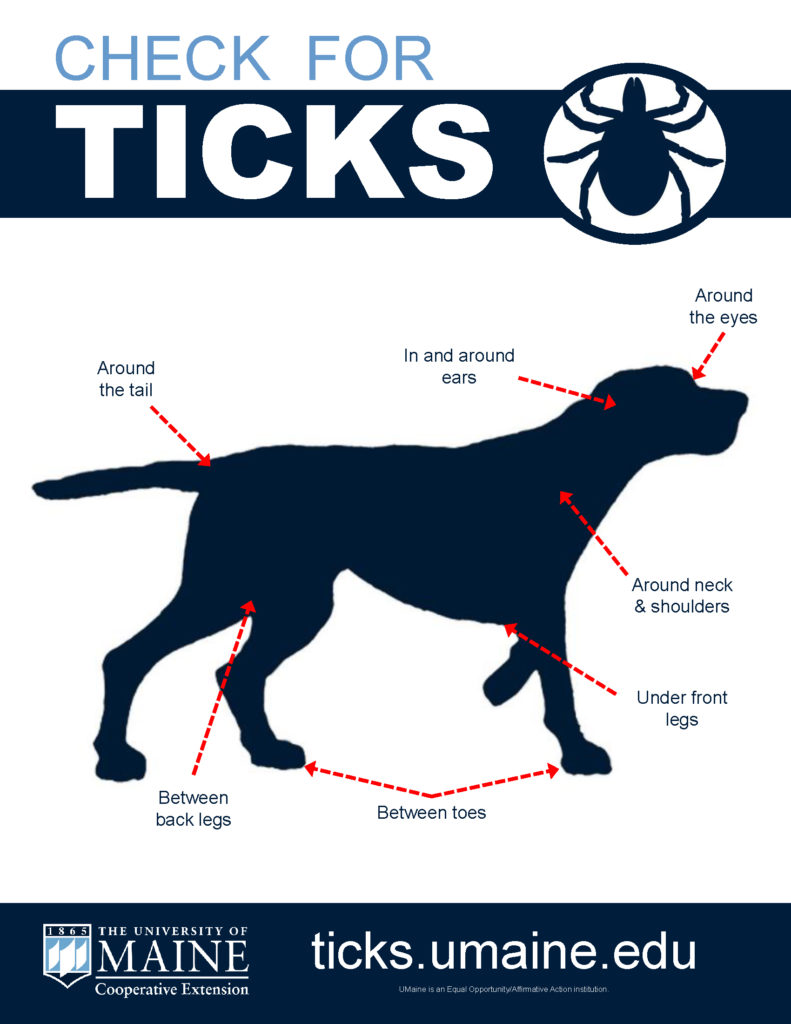

Per the CDC, “ticks can attach to any part of the human body but are often found in hard-to-see areas such as the groin, armpits, and scalp.” The moment a tick attaches, the clock starts ticking on disease transmission. That means the sooner – and more often – you do a tick check, the better. At the bare minimum, a good rule of thumb is to do a quick tick check every time you come inside after spending time outdoors in a natural area. It’s also important to check your pets, particularly dogs.

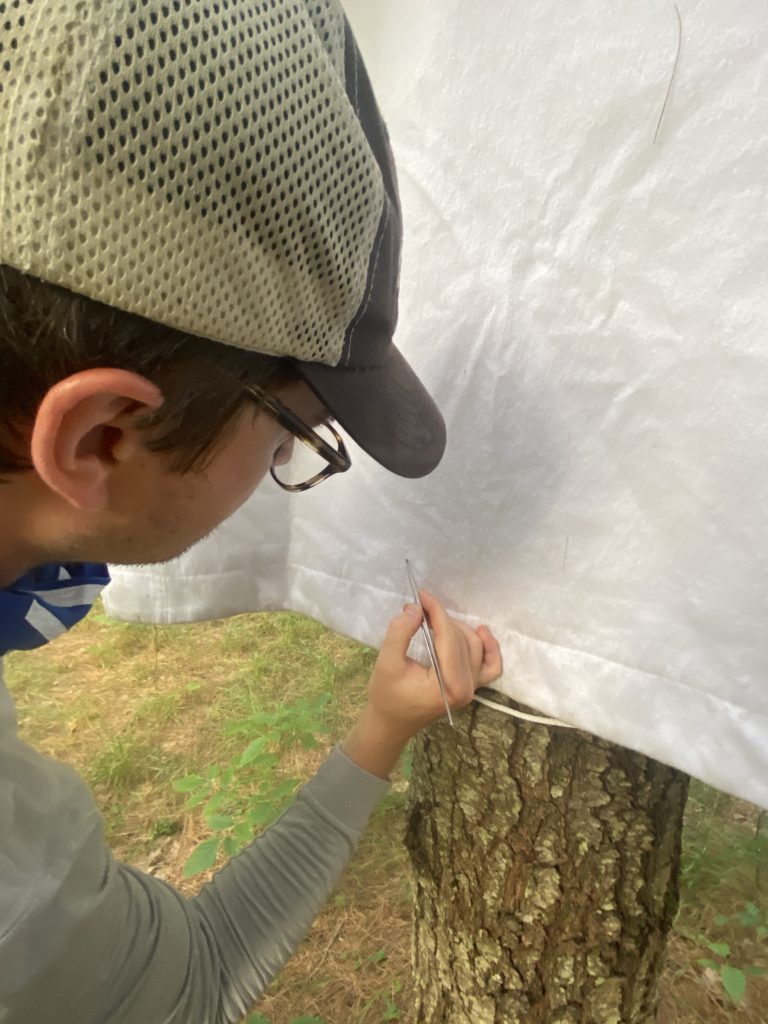

Author’s Note: I do tick checks several times a day, especially when I am working on CELT properties off the trail. So far this year I have found 10 ticks on me, including three attached. Because I do tick checks so regularly, I am confident that none of those three ticks was attached for longer than six hours, meaning my risk of disease is very low.

Preventing Tick Encounters

This section is quoted directly from UMaine. “The most important consideration in reducing tick encounters is the use of personal protection strategies. By taking a few simple precautions, you can significantly reduce your exposure to ticks.

Avoid Direct Contact with Ticks

- If possible, avoid tick-infested areas or areas you believe may be infested with ticks.

- If unavoidable, plan activities involving tick habitat for the hottest, driest part of the day.

- Avoid walking through wooded and brushy areas with tall grass and leaf litter.

- Walk in the center of mowed or cleared trails to avoid brushing up against vegetation.

Dress Appropriately

- Wear light-colored clothing to make ticks easier to detect.

- Wear long pants tucked into socks or boots and tuck your shirt into your pants to keep ticks on the outside of your clothes.

- Do not wear open-toed shoes or sandals when in potential tick habitat.

Use Tick Repellents

- Use products that contain permethrin to treat clothing and gear. Do not apply permethrin directly to your skin.

- The use of repellents that contain 20-30% DEET on exposed skin and clothing can effectively repel ticks for several hours.

- Other tick repellents recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) include picaridin, oil of lemon eucalyptus, and IR3535.

- When using repellents, always follow label directions.

- For more information see our fact sheet on insect repellents.”

For more information on tick prevention visit the UMaine website.

In Conclusion…

Ticks are everywhere, and they can carry dangerous diseases, but there are a lot of things you can do to protect yourself and adapt to living with ticks. There’s always some risk to going outside, but by following the guidance above (and learning more from other resources) you can make sure that risk is kept at a safe level.